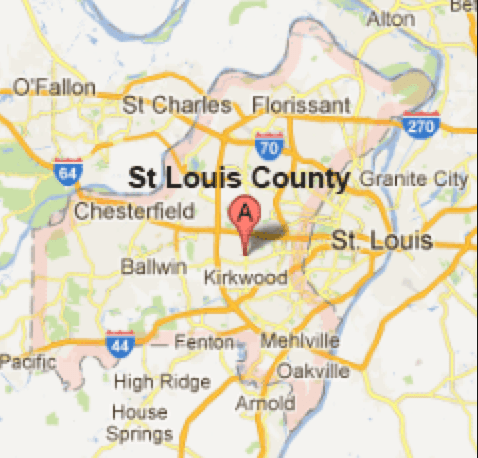

Seventy-five years ago St. Louis mounted a great effort to rid itself of air pollution that had plagued the city, and many others throughout North America and Europe, for decades. This is the last in a continuing series about that campaign.

By Bob Wyss

In June 1941 the Chrysler Corporation wanted to do a radio program, as part of its continuing series honoring cities, on St. Louis and its air pollution campaign.

The introduction began: “St. Louis had – figuratively speaking – washed her face. For within the past year she has very skillfully wiped out the plague of smoke and soot that dimmed her skies.”

Coal officials objected. A flurry of telegrams was sent to Chrysler arguing that the smoke problem had not been resolved and that the city ban on high sulfur coal was creating dissension. Even mentioning the smoke program, said C.V. Beck of the Illinois Coal Trade Commission, would be an attack on the coal industry.

The coal industry had been waging an unrelenting attack on the St. Louis campaign and despite its failure those arguments would continue for years. Echoes of the drive could be felt decades later when concern how coal was warming the planet produced million-dollar complaints in a campaign called “The War on Coal.”

A truck passes a political sign in a yard in Dellslow, W.Va., on Oct. 16, 2012 as workers and their employers joined forces in the public relations campaign called The War on Coal. AP Photo

In St. Louis most of the defense was placed on two men, Raymond Tucker and James L. Ford Jr. Tucker was smoke commissioner until September 1941 when he resigned and became a consultant working to help other cities adopt ordinances and campaigns similar to the one in St. Louis.

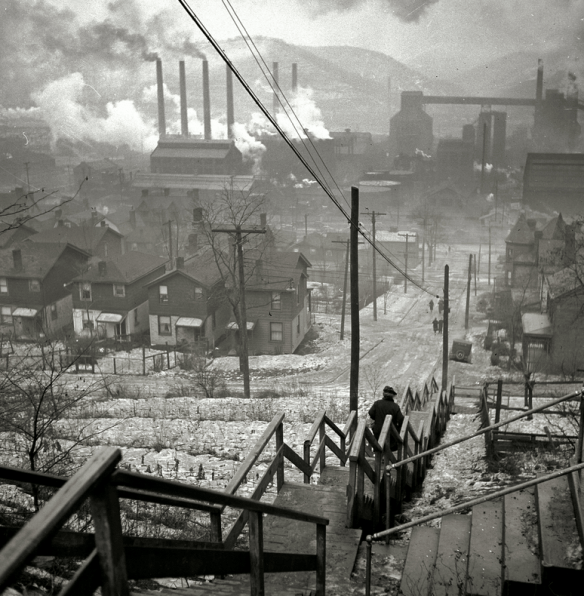

Pittsburgh, long known for its foul air pollution, was one of the first to pass a similar ordinance. Tucker was a consultant to the city at the time.

Ford was a banker who had been drafted to become chairman of the Smoke Elimination Commission in St. Louis. After Tucker began evangelizing through the nation much of the defense in St. Louis fell to Ford.

And there were attacks, repeated attacks, by the coal industry, which wanted to return to business of the past.

One of the first came in August 1942 when a coal industry trade publication, The Solid Fuel Engineer, published an anonymous letter arguing that the city should relax its ordinance and allow dirtier coal to be burned until World War II ended. Later the magazine’s editor joined the fray arguing that the ordinance had not significantly reduced air pollution, despite the claims of the city.

Other attacks came in 1944 and in 1947 even after the war was over.

There were a variety of charges made but the harshest seemed to be that the air quality had not improved in St. Louis in the 1940s. It was also the easiest for Tucker to disprove.

In the winter of 1939-40 when St. Louis was often buried for day after day under thick bilious clouds of black smoke, the number of hours recorded by the U.S. Weather Service was 599. That had been cut to 127 hours by 1942-43 and was only 156 hours in 1944-45.

Other cities did adopt the St. Louis ordinance but ultimately the smoke problem that had plagued cities throughout North America was resolved not by burning cleaner coal but from adopting a new fuel. By the 1950s the natural gas industry was building a network of pipelines that would crawl across America, delivering a cleaner, cheaper and more convenient fuel. No longer would coal trucks have to drop huge piles of ore, no longer would someone in a household need to bank the burner each night, no longer would the ash have to cleaned and dumped outside.

Former Mayor Bernard Dickmann, dumped from City Hall partly because he forced voters to buy more expensive coal, was rewarded in 1953 with a patronage job as St. Louis postmaster. He would serve 15 years. Ford, the banker and reluctant public servant, could retire. Tucker would go into politics and become mayor of St. Louis from 1953 to 1965.

But while coal would no longer be burned in homes and small businesses, coal did not disappear. In 2015 the U.S. produced 895 million tons of coal, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That has decreased from the peak in 2008 of 1.17 billion tons, but is still twice as much as what was being produced in the early 1940s.

A

A mountaintop removal mining site at Kayford Mountain, W.Va., representative of how coal has tried to become more economically feasible and yet less environmentally acceptable. AP Photo

With concern continuing to rise over coal’s contribution to global climate change, coal production is expected to continue to decline. But just as in St. Louis, it is not going to go down without a fight.

“The War on Coal” public relations campaign against increased environmental regulations and oversight is also a well-financed investment by the coal industry. The Center for Responsive Politics reported that the money surges in election years with $11 million spent in 2014 and $15.3 million in 2012.

One can only wonder how much will be spent in 2016 with the general election still ahead at this writing.

For 16 months coalblacksky.com has tried to shine a light on a past that for most has been long forgotten. We take our air for granted and yet without it we would perish.

For decades in the past cities across America took it too much for granted. The result was a long history of illness and death.

In St. Louis courage and fortitude found a way out of that dilemma.

Today the attack in the air we breathe is far more insidious, far less noticeable, and in some respects far more dangerous.

It would be inexcusable to leave such a legacy for those who will follow us 75 years from now. We have to find the spirit and pluck to end all coal black skies.